Residents and businesses are asking community leaders for competitively priced, affordable, and reliable broadband services to support all connectivity-dependent uses, including work, education, health care, and business—and deliver ever-increasing capacities. In today’s world, that means gigabit per second (Gbps) symmetrical services, far beyond the Federal Communications Commission’s outdated 25 megabit per second (Mbps)/3 Mbps national standard. Clearly, communities will not be competitive in attracting new residents and business investment without world-class broadband.

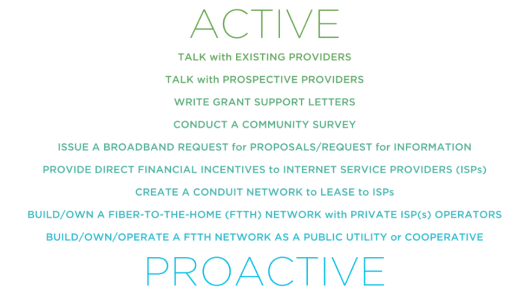

There are multiple pathways, ranging from Active to Proactive, to better community broadband infrastructure. Here are some examples:

ACTIVE

ACTIVE

Talk with existing providers

Talk with prospective providers

Write grant support letters

Conduct a community survey

Issue a broadband request for proposals/Request for information

Provide direct financial incentives for Internet Service Providers (ISPs)

Create a conduit network to lease to ISPs

Build/own a fiber-to-the-home (FTTH) network with private ISP(s) operators

Build/own/operate an FTTH network as a public utility or Cooperative

PROACTIVE

This handbook focuses on the steps that can lead to a publicly owned broadband network. While every community will take its own unique path, there are well-established critical steps necessary on a successful decision-making and implementation journey.

There is not a single definition of public broadband. While some consider a public broadband network to be only networks owned and operated as a public utility with the public entity as the Internet Service Provider (ISP), the AAPB includes many public-private partnerships and cooperatives under the category of “public.” For the AAPB, the common denominator is that the community owns some portion of the communications network infrastructure. Public-private partnerships in which the public role is limited to providing a financial subsidy to a private-sector network owner/operator would not be considered in this definition.

Public officials are often too quick to discount the public broadband option. Discarding this option too early bypasses consideration around a wide array of public network benefits and surrenders a valuable negotiating tool in dealing with incumbent providers.

Hesitancy factors:

- Lack of technology knowledge

- Time and expense necessary to determine feasibility

- Uncertain path forward

- Fear of taking on significant new government responsibilities

- Fear of multimillion-dollar network construction costs and public debt

- Incumbent provider lobbying

- Public-sector broadband challenges

- Lack of awareness of success stories

Communities may find that by just considering a public broadband network, they may bring increased attention from incumbent providers and stimulate short-term network investments and promises of more upgrades. These public discussions also attract prospective ISP partners and discussions of public-private partnership.